Microsoft's 'Muse' Project Explained, and the Poor Quality of AI Reporting | AI and Games Newsletter 26/02/25

Plus Monolith's closure, the 'Make it Fair' campaign, and more.

The AI and Games Newsletter brings concise and informative discussion on artificial intelligence for video games each and every week. Plus summarising all of our content released across various channels, like our YouTube videos and in-person events like the AI and Games Conference.

You can subscribe to and support AI and Games on Substack, with weekly editions appearing in your inbox. The newsletter is also shared with our audience on LinkedIn. If you’d like to sponsor this newsletter, and get your name in front of our audience, please visit our sponsorship enquiries page.

Greetings one and all and welcome back to the

newsletter. I had planned to spend this week talking about the responses to the GDC State of the Industry and what meant in the space of AI for game development. But hours after we published last week’s issue, Microsoft set the internet ablaze with conversation surrounding their latest AI research: a generative model called Muse which aims to reproduce the behaviour of a pre-existing video game. With Xbox gaming head Phil Spencer suggesting it could prove valuable as a mechanism for game preservation.So of course we’re a week behind on the discourse - thanks Microsoft, could you not have given us a heads up? (wink) - but that’s arguably better for us given it gave some time to read up on the project, and provide a more nuanced take. So let’s get going as we dig into the news, all the regular stuff and then what this Muse thing is all about.

Follow AI and Games on: BlueSky | YouTube | LinkedIn | TikTok

Announcements

Time for all the regular updates of all things in and around AI and Games!

New Conference Talks Live on YouTube

We continue our run of releasing two new videos on the AI and Games Conference YouTube channel each week to celebrate the fantastic presentations from our 2024 event. Last week we had an EA double-bill, but this week it’s courtesy of the good folks at Guerrilla!

Tim Johan Verweij, a principal AI programmer at Guerrilla presents an overview of the studios implementation of Hierarchical Task Network (HTN) planning in the Decima engine - used in games such as Killzone: Shadow Fall, Horizon Zero Dawn, and Death Stranding.

Meanwhile David Speck, one of Guerrilla's senior AI programmers, gives us a deep-dive (no pun intended) into how machines fly and swim in Horizon Forbidden West.

Thank you once again to both Tim and David for speaking at our event. Both talks are of fantastic quality and I was so excited and grateful to have the studio’s AI team commit their time and energy to our event.

Quick Announcements

Taking a quick moment to thank everyone who has continued to support Goal State while late pledges are still live on Kickstarter. We are now only 10 backers away from unlocking another stretch goal, which is to create an hour-long deep-dive video into the AI source code of Half-Life. Late pledges will continue to run for the immediate future so if you’re interested, be sure to check it out!

With only a couple of weeks to go until the Game Developer’s Conference, I’m finalising my schedule for meetings and such while in San Francisco. Happy to arrange a get together to discuss any of the following:

Providing technical and/or research consultancy for your project.

Running professional training on AI in your studio.

Partnerships on our YouTube and/or newsletter.

Sponsoring or presenting at the AI and Games Conference

Or just a proper bit of banter over some coffee.

Book now by clicking this here button!

AI (and Games) in the News

Not that many headlines in the news this week, but let’s quickly report on them.

Call of Duty (finally) Admits Using Generative AI

As discussed last year, there was a bit of a furore surrounding some of the cosmetics in Black Ops VI’s holiday event given it looked like some of it was made using generative AI tools. While as mentioned in the VGC article it’s only been spotted now, but Activision updated the AI disclosure on the Steam page in late January. I have since noticed that some of the other items for sale, notably things like emblems and backgrounds, appear to be using generative tools (i.e. they look pretty cruddy). So I think we can expect this to continue.

The ‘Make It Fair’ Initiative Launches, with Zero Video Game Involvement?

Yesterday was the final day of the UK’s open consultation on AI and copyright, a topic we discussed at great length last month. I hope you took the time to share your concerns if a) you’re British, and b) you had concerns!

As mentioned in this issue, the UK governments plans have not been well received, and to that end the ‘Make it Fair’ campaign launched yesterday. Launched by the Creative Rights in AI Coalition, a collection of bodies across press, creative industries and other affected sectors, seeks to engage with the government on building a “long-term, secure growth in the creative and tech sectors” for the country, by ensuring that the robust processes and sensible practices are put in place for a future in which generative AI will continue to flourish.

The big takeaway from this? The coalition includes several high profile newspapers, the associated press, membership bodies representing academic publishing, professional book publishing, photography, television, motion pictures, music, and somehow… no video games representation whatsoever.

It speaks to what is a strange situation where even now you won’t find many large video game companies - or their trade representatives - speak up on these issues.

WB Games Closes Studios to Mitigate Poor Business Strategy

There are few media companies with the IP catalogue of Warner Bros who equally fail to capitalise upon it successfully. As their games division has suffered from one poor business decision after another - doubling down on mobile and live service titles such as Suicide Squad and Multiversus while their only major success of recent years was the single-player story-focussed Hogwarts Legacy - the solution to these financial challenges is to… stop making games?

Last night Bloomberg’s Jason Schrier broke news that WB Games is closing down several studios as part of their broader strategy. Closing the still relatively new WB San Diego, Multiversus developer Player First Games, and finally Monolith Productions who in recent years have been working on a game based on the Wonder Woman IP.

This last one is a real stinging point for me, and the broader AI and Games community, given Monolith have been responsible for many interesting games in their roughly 30 year history, with titles such as Blood, No One Lives Forever, F.E.A.R., Condemned: Criminal Origins, The Matrix Online, and Middle-Earth: Shadow of Mordor. We’ve talked about F.E.A.R. at great length here on AI and Games over the years given it is one of the most influential titles of all time in the sphere of AI character behaviour.

The full story is now live on Bloomberg.

Microsoft’s Muse: The Generative AI Model to Support Gameplay Ideation

So yeah, this week let’s get into one of the biggest talking points in AI of the past week or so, given it intersects heavily with games. On February 19th Microsoft published work by the team at Microsoft Research on what is known as ‘Muse’, a generative model that is capable of simulating aspects of a game it has been trained upon.

Much has been said of this project since its publication a mere week ago, and so I felt it best to dedicate this issue to a deeper-dive into the work itself. So let’s discuss the following:

What Muse is, and how it actually works.

What Microsoft has done thus far using the Muse model.

What Muse is not, and tackling some false narratives that have emerged.

How reporting on this project has completely lost the nuance of the original work.

Disclaimer: As always I approach this weeks topic with the intent to give clarity, insight, and balance to the subject at hand. But it’s important I disclose that I know some of the authors of this research.

What is Muse: In Short

Muse is the term given to a new type of generative AI model developed as a collaboration between the Teachable AI Experiences (Tai X) and Gaming Intelligence teams at Microsoft Research (MSR). The actual model, is what the researchers refer to as a World and Human Action Model (WHAM). The model is able to simulate the behaviour of a video game within a limited scope of execution, and simulates how the game would behave over a period of time, offering both the visuals (at a low range of fidelity), and/or the action inputs themselves from users as they ‘play’ it.

To stress test the efficacy of the system, particularly as a means to support game developers in coming up with new ideas for their games, the researchers collaborated with some of the development team behind Bleeding Edge, an online shooter developed by Ninja Theory, which is one of the many games companies that exist within Xbox Game Studios. But critically, they’re both in Cambridge here in the UK.

The research used around seven years of data on how people play Bleeding Edge and then trained a WHAM model that can simulate the game in a way that is not only consistent, but can take on modifications from humans and it will attempt to retain that modification in the simulation it creates.

You can hear a little more from Microsoft themselves in this video below with Xbox lead Phil Spencer, Dom Matthews (studio head at Ninja Theory), and Katja Hofmann from Microsoft Research.

What is the Research Actually About?

The point of this work was to address an issue that occurs a lot with how generative AI works. In that trying to use a generative model can often be difficult in creative works, because it’s seldom capable of maintaining a consistent output, or preserving key pieces of information that are important to the creative process.

For example, a point I make when running training courses in using generative AI systems, is that the value of any output is heavily dependant on the input. For instance take text generation like GPT. It’s hard to get it to generate something that really reflects your needs lest you take the time to query (or rather, prompt) the model with clear context and direction of start and end-points. This is all the more relevant when building narrative. You cannot rely on a large language model (LLM) to retain all of the key information to build an entire story, because it can’t retain the context of the story and maintain its consistency in the long run. However it is good at maintaining context and critical knowledge over shorter term. Hence why one of the biggest areas for exploration comes in smaller chunks of connective narrative or incidental dialogue.

So how would all of this apply to video games? Well the researchers interviewed a collection of game developers about the viability of generative AI as a means to support ideation: of coming up with new ideas and experimenting with new concepts for a game. The biggest takeaway from those interviews was how generative AI tools are seldom practical in ideation, given a lot of lateral problem solving occurs on an almost daily basis - and most generative AI tools can’t keep up with the needs of creatives. Ideation often means making small but meaningful changes to a games design and then seeing what kind of outcome that yields and whether that outcome is interesting.

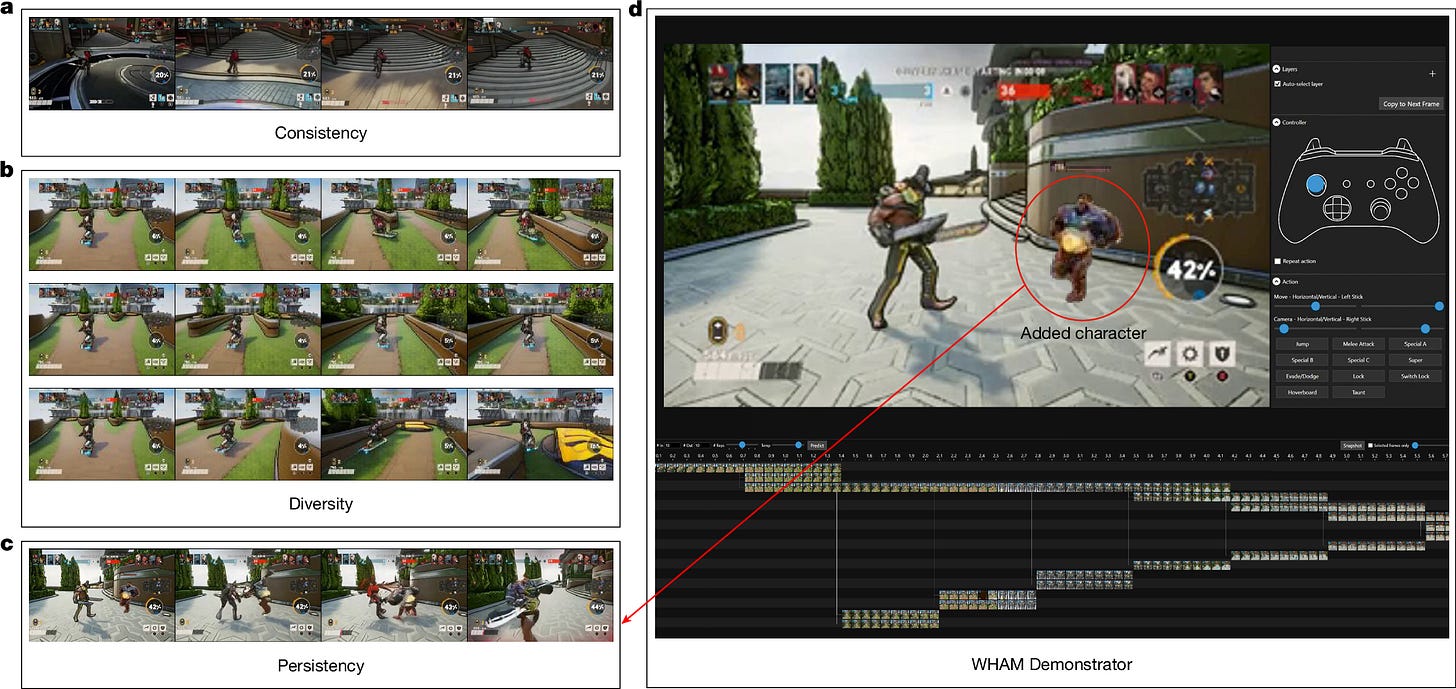

From this idea, MSR sought to build a generative model that can address this. Perhaps critically, from these conversations, MSR then adopted three criteria for any generative AI tool to support ideation for game development:

Consistency: The model generates output that retain the provided context.

Diversity: The model generates ideas that are suitably varied and diverse.

Persistency: The model can take changes provided by designers and retain them in the ideation.

So the team built a generative AI model known as a WHAM: World and Human Action Model. The WHAM is trained on a large amount of human generated gameplay data (i.e. the data you create just by playing the game). In fact it was trained on approx. 500,00 anonymised game sessions, amounting to around 7 years of one person playing the game continuously. From this data, it attempts to predict both what the future visual frame of the game might look like, but also what actions or inputs the player made to make that next frame materialise. This is, to an extent, how humans come to understand how games work, such that we internalise the logic of the game through observation. The WHAM model in essence achieves that to a certain level of fidelity.

WHAM is built using a transformer architecture, the same type of AI system as that used by GPT, and in this example was trained solely on data of the Bleeding Edge game across all seven maps players can compete within. The largest version of WHAM, amounting to around 1.6B parameters, can then generate the output ‘frames’ of the game at a resolution of 300x180 pixels. Meanwhile a smaller version which only trained on a single map (SkyGarden) renders at 128 x 128 pixels.

The team then evaluated whether or not the model addresses the three issues raised above.

Consistency: The model can generate sequences that are consistent with how the game operates, in the best cases up to two minutes long.

Diversity: Assessed both quantitatively and qualitatively, they found that the generated sequences would vary in terms of the behaviour exhibited by the ‘player’, as well as showing visual diversity such as changing the colour of specific elements of the games visual design.

Persistency: This was the real litmus test for whether the model would prove of interest for game designers. To evaluate this they manually edited single images of the game by adding in new elements that previously were not there before, such as a collectable item or a map element like a jump pad, and then evaluating whether the system could then generate a sequence that retained that knowledge.

All of this was then put to the test courtesy of the WHAM Demonstrator (great name), that is shown in the video below. This showcases how these three aspects operate in context.

This is but a high-level summary. Stick around as we’ll run a deep-dive into the paper as the focus of a future publication here on

.What Muse Is Not: Some Mythbusting and Quick Talking Points

One of the things that cropped up really quickly - which I will discuss in more detail below - was how the narrative surrounding Muse was how it was ‘anti-gamedev’, or that it was seeking to undermine the works of creatives by building generative models, and I wanted to address these quickly. Almost every hot take I’ve seen on this work is not accurate, at all.

Muse Is Not Generating ‘Games’

As discussed above, the WHAM model doesn’t make games. It simulates an existing game, and then generates sequences of visual and actions that are evocative of a game. Plus they all make sense in context of the game that it was trained on. It can’t create new games from scratch, nor is it actually creating games.

Muse Is Not Even Generating ‘Gameplay’

As mentioned it generates a sequence of visual frames and the actions that link with them. This isn’t necessarily gameplay, it’s simulating the perception it has of how people play a game. Of how gameplay exists as a relationship between the game and the player, and from that it provides a platform on which to allow a human to see how that gameplay could change as a result of making small tweaks to the pre-existing laws and behaviours of the game’s systems.

Muse Doesn’t Even Generate ‘Ideas’

As much as the research is about ideation, and enabling processes for game developers to ideate within, the WHAM model doesn’t create ideas. The research is really about evaluating what are the current limitations of generative models such that a creative person may find it useful as an ideation tool. It doesn’t come up with the modifications made to the game that it then preserves. A human is doing that.

It’s Not a Solution to Game Preservation

Despite Phil Spencer’s comments in the video above, Muse as it has currently been developed and published is not about game preservation. It’s about providing an alternative means to support game ideation, by providing a rough simulation of the game.

They Can’t Just Build This For Any Game Overnight

One of the wildest theories I’ve seen, no doubt derived from the Spencer’s game preservation comments, is that Microsoft is going to start generating all sorts of Muse models overnight. That’s really not plausible. As mentioned above, this is running off half a million gameplay replays. Seven years of gameplay of a single game. But also, it’s a game that isn’t changing or evolving over time.

One of the big reasons that Bleeding Edge is a good use case for this, is that the game is effectively ‘done’. It’s still playable on Steam and Xbox, but the game itself hasn’t been updated in close to five years (September 2020). And that means that it’s in a stable enough condition that the gameplay data can be generated and learned from.

This is a point I have raised several times with this sort of work, in that the game itself needs to be in a decent enough condition, and remain in that condition, for the AI to learn from it. Referring back to the work on StarCraft II by Google DeepMind, the AlphaStar bot never re-appeared because it as soon as the game was patched for a new season, the ‘meta’ would shift so drastically that it would warrant re-training (at a great expense).

My Initial Thoughts

As you’ll know if you’re a regular reader of this newsletter I am very critical of the ‘shoot first, ask questions later’ approach that many company’s have taken towards generative AI in the creative industries - and especially games, given that’s my jam. But in this instance I’m quite intrigued by this work. The research effort is very much, at its core, about identifying the limitations of generative models as being practical or useful in creative industries, and especially games. So the fact that this team is exploring what needs to be done to make this sort of thing even remotely palatable is very much my jam.

Do I think this is practical? No, because it’s far too early for it to be relevant as an actual tool for a developer. But its existence as a research tool to help further the conversation on AI viability is certainly interesting. And I’m keen to see where it all goes. But on the face of it, I think it’s an interesting project, and I like that MSR has sat down with game developers to try and work on a viable solution for generative models, rather than simply publish something and then try to spin it after the fact like Google’s Genie 2 from last year. Though as we’ll discuss shortly how it has been promoted has presented unnecessary ire.

The idea of computational co-creativity, of having AI systems interact with humans in the process of a creative pursuit, is a well worn one. There is literal decades of research in this area, and this is very much building on those ideas. The paper itself refers back to much of the literature and existing practices used in this field, and so it is very much contributing to an ongoing academic conversation. One that has been around for quite some time now.

And this is the crux of much of the furore surrounding this project, in that the conversation is typically behind closed doors in academic circles. But this has presented much more broadly, and has been prone to miscommunication.

How Reporting Obfuscates Reality

In the closing weeks of last year I wrote about my issues with how developments in AI are often discussed and promoted in ways that don’t align with reality. A research project can have some interesting ideas at its core, but it is then promoted or marketed in ways that don’t align with what it can actually do, or how the ‘real’ world works.

I quote from the article linked below, in which funnily enough I was discussing Genie 2, a generative AI model that is on a surface level similar to the WHAM model MSR built.

I won’t denounce Google for building a weird research toy that is impractical for the real world, because that is what a lot of research is. It’s about exploring ideas and then sometimes finding ways in which it could prove useful in specific use cases - be it in leisure, business, healthcare, whatever. So many useful, practical, and relevant applications of technology - be it AI or any other discipline - emerge from researchers exploring weird and wonderful ideas. And in fact a lot of ideas are eventually discarded: because at the end of the day it’s an interesting concept that just doesn’t ‘work’ when you place it within the trappings of real world scenarios.

But I will denounce Google for the manner in which it presents its work, and the company’s messaging of how their work could impact broader business and society. If Genie 2 was a piece of research published 20 years ago, it would have been an exciting update that you really would only hear about within academic spaces. That they had built something that many a researcher would be inspired by and explore in their own work. But in 2024 we operate in a very different climate. Now something like Genie 2 or Sima gets a PR push because it influences stock price, and the broader perception of Google’s impact in a rapidly developing field. Without any meaningful consideration of whether the messaging behind the PR is going to negatively affect existing industries and processes. Because the goal is to get people talking about it, regardless of how useful it is in any real world situation.

I raise this because there is a distinct difference between what Muse is actually doing, the way in which it has been communicated, and how the press subsequently report on it. To summarise some of the headlines I’ve read surrounding Muse both from Microsoft itself and then from other related outlets within the first 24 hours of its announcement.

Microsoft’s Muse AI can design video game worlds after watching you play [VentureBeat]

Microsoft’s Xbox AI era starts with a model that can generate gameplay [The Verge]

Microsoft is replacing human gamers (and even games) with AI [PCWorld]

Microsoft says it could use AI to revive classic Xbox games [VGC]

Muse is Xbox’s generative AI model for gameplay ideation [GamesBeat]

Microsoft wants to use generative AI tool to help make video games [New Scientist]

I point this out because it’s equally as interesting as it is unsurprising how quickly the core of what Muse does, as I discussed above, is lost in the reporting on it. These headlines range from reasonably accurate (GamesBeat, Polygon), to what I would argue are misrepresentative at best (The Verge, New Scientist), and outright rage bait at worst (PCWorld). This isn’t to defend Microsoft per se, but rather to point out how quickly - within hours of the original announcement - the nuance of what Muse is actually about, is immediately lost.

The conversation online is now about how Xbox has made either a game ideation machine, a game generator, or both? Neither of these is what the WHAM model really is, but it speaks to both the general apathy among (very online) creatives, combined with the general misunderstanding of what AI does, that we reach those conclusions so quickly. This is largely because of the trajectory of many corporations in AI deployment, and how often we see rather overzealous adoption without meaningful applications.

I Don’t Think Even Microsoft Understands What Muse Is

Returning back to what Phil Spencer said about using it for game preservation, I’m now sitting here scratching my head as to how that was the takeaway from all of this. Yes, you could argue that by gathering up sufficient amount of recorded data about any given game you can generate a WHAM model that simulates it, but as the Microsoft Research team mentions in the paper, the purpose is focussed on building an ideation tool and at present the model can only generate sequences of up to two minutes consistently (which, fair play, is really impressive).

It seems like in an effort to show other potential use cases, they’ve pitched this idea of it being a preservation machine, which sort of undermines what the MSR team were doing on the project. At no point in the published research paper does MSR suggest this is a games preservation solution. Plus as stated, nothing about this technology in its current form would enable reproduction of games at quality and at scale to make it a practical product for playing games, much less preserving them.

Having Phil Spencer come out and imply it's a potential future means of game preservation was a real misstep on their part and only stoked the flames. It really fails to grasp the work people do in game preservation (see PhD student Florence Smith Nicholls work in 2023 on working to curate games at the British Library). In time perhaps a model could allow people to 'play' a game without the need for literal emulation - and could be a curio they publish on Game Pass - but it's really not what people in and around that community are interested in, nor is it really feasible at this time.

This was made even worse just last weekend as VGC and other outlets reported on Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella’s appearance on the

where he presented what is again an exaggerated and inaccurate take on what this work is doing. In this interview Nadella discusses with host Dwarkesh Patel a number of topics related to Microsoft’s overall overall AI approach and strategy. Critically in context of Muse, Nadella says the following at around the 43 minute mark:Nadella: I think we're going to call it Muse, is what I learned, is they're going to be the model of this world action or human action model. And... It's just very cool. See, one of the things that, you know, obviously DALL-E and Sora have been unbelievable in what they've been able to do in terms of generative models. And so one thing that we wanted to go after was using gameplay data. can you actually generate games that are both consistent and then have the ability to generate the diversity of what that game represents and then are persistent to user mods, right? So that's what this is.

And so they were able to work with one of our game studios. And this is the other publication in Nature. And The cool thing is what I'm excited about is bringing, so we're going to have a catalog of games soon that we will start sort of using these models or we're going to train these models to generate and then start playing them. And in fact, when Phil Spencer first showed it to me, where he had an Xbox controller and this model basically took the input and generated the output based on the input and it was consistent with the game.

And that to me is a massive, massive moment of, wow, it's kind of like the first time we saw ChatGPT complete sentences or DALL-E draw or Sora, this is kind of one such moment.

So the problem with Nadella’s comment is that, again, he has taken what works in a very specific fixed scenario: simulating gameplay sequences from a single game and has extrapolated that into a narrative that implies this idea will be applied to other games in production, and that it is generating a playable game.

It’s a stretch of the imagination, and without any real consideration for business economics - how expensive and time consuming is it to build these models for every game being made under the Xbox banner? Plus failing to read the room around a gaming audience who are aware of the economic volatility of the market right now, who are already sceptical of AI, and then being told that AI generated content may well be the future.

Again, I think the Muse project is getting a lot of flak having been dragged into a conversation it didn’t intend to be a part of. If any effort was made within Microsoft to manage the message of this research, then they have spectacularly failed in that regard.

I Owe the Muse Team An Apology

I want to take a moment to highlight that I fell afoul of listening to the narratives that quickly sprung up when this was announced. My social media blew up in a far from positive way after Muse was announced, and I made some comments both on BlueSky, as well as in my Discord server, that in hindsight I don’t agree with - and I’m keeping them there for posterity.

In hindsight this reads as very cynical, and I’m actually ashamed that I jumped to that so quickly. Critically, I jumped to that conclusion without reading the paper. Having now read the works in much more detail, I recognise that my perspective on this was completely wrong, and I’m much more interested in the work now than I was when it was first announced.

But this speaks to the inherent problem. In that the reporting surrounding this was so completely off base that, regardless of whatever mood I was in, I let it get the better of me. And I didn’t conduct my due diligence before I spoke up. So as my closing remark on this - for this week anyway - I wanted to apologise to the authors. I need to do better moving forward!

Want to Know Even More?

If you have the background or persistence to do so, I recommend reading the original paper from Microsoft Research published on Nature.

Wrapping Up

Wooft! That was a lot of writing, and critically this took up a good chunk day or so of my time to put together. I should get back to doing everything else I’m meant to be doing.

On that note, we will have an update for Goal State backers later this week as we summarise where things are with the development of Game AI 101 course! Until then, thanks for reading and we’ll catch you next time!

I really liked how you demystified Muse's misconceptions and how this kind of misinformation about AI as a whole is spread across news outlets and social media. There's a lot of extrapolation exercises or there that passes as facts, something that unfortunately occurs with every new technology in history, and seems to be worse when the subject is AI. Having thoughtful articles like this are a great way to steering the conversation to the right path.

In any case, the Muse applications seem very promising! This reminded me on my early days as a game designer when the engines had just a fraction of features a modern engine has nowadays. We needed to do a lot of work that new tools and libraries execute with just a few clicks. Projects like Muse should be welcomed by its power to relieve some of the hard work game designers have to create great experiences for players.

Anyway, great article! Thanks for sharing it!