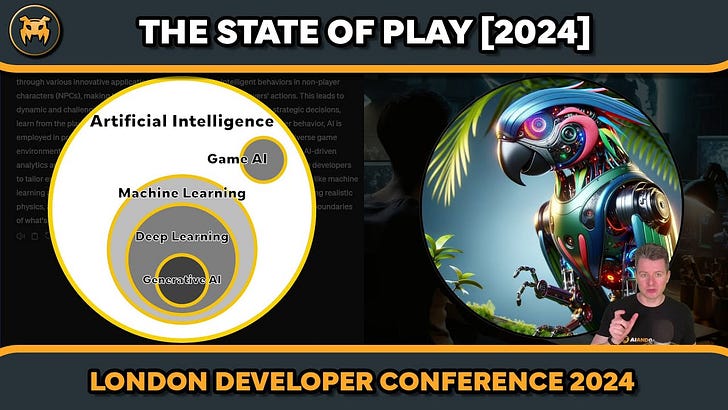

Digging into Project AVA: The Game Made (Almost) Entirely with Generative AI | Weekly Newsletter 08/05/24

One of the most interesting talks about Generative AI at GDC

The AI and Games Newsletter brings concise and informative discussion on artificial intelligence for video games each and every week. Plus summarising all of our content releasing across various channels, from YouTube videos to episodes of our podcast ‘Branching Factor’ and in-person events.

You can subscribe and support AI and Games right here on Substack, with weekly editions appearing in your inbox. The newsletter is also shared with our audience on LinkedIn.

Hello all and welcome back to another edition of the AI and Games Weekly Newsletter. Today, I wanted to focus on what was, for me, one of the most interesting talks at this years Game Developers Conference. But first, let’s get into some announcements and everything else I have to share this week. After all, there’s never a quiet week here at AI and Games, that’s for sure!

Weekly Announcements

Over on our podcast ‘Branching Factor’, I am joined this week by co-host Quang, as well as game developer and journalist Jupiter Hadley to talk about the Brilliant Indie Treasures: a free event showcasing over 50 indie games running this July in the UK.

A reminder that the Barclay’s Games Frenzy is tomorrow on May 16th in London. I’ll be around and happy to chat to people wanting to talk some more about AI for games.

Another reminder that registration closes for the AI and Games Summer School on May 17th. Be sure to visit the website to sign up and attend the event in Valletta in Malta from June 17th-21st. I am going to be in attendance and hosting a panel discussing relevant topics on AI for games with a number of the events invited speakers. See you there!

Plus to reiterate my point from last week, I’d love to do a special issue rounding up the Foundations of Digital Games conference. If you’re a researcher attending the conference and would like to share your work, please drop a line!

Please get in touch either by messaging me on Substack via the button above or on LinkedIn. Give us a short paragraph about what your research paper is about, plus some links to relevant assets (the paper/videos/images etc.) that we can share with the audience.

Project AVA: The Game Built Using Generative AI

For this weeks main event, I wanted to dig into one of the more interesting talks I saw at GDC - outside of the AI Summit of course*. In recent weeks I’ve been rather doom ’n’ gloom with generative AI for games - which sadly is often highly justified. So I figured let’s spend this week talking about something positive!

As part of my work with video game companies, I am frequently being asked about the viability of generative AI tools, and what opportunities exist to employ in smart, practical, cost-effective, and ethical ways. Despite the issues that I have discussed at length elsewhere - namely the quality of the tools, access via web APIs, IP protections, value for money, and the commercial and legal viability - there is a path to safe execution and practice in early ideation and iteration of a studio project. But right now, quite often there are too many risks for a studio to replace their existing pipelines with generative AI tools.

* I’m on the organisational committee for the AI Summit at GDC, so I knew in advance that all our talks were going to be awesome.

However, at GDC we had a talk about a game called ‘Project AVA’, which was achieved by doing exactly that. A game built only through use of generative AI tools… mostly.

Project AVA was developed at Keywords Studios, a company that you may not have heard of until now. Keywords is one of the largest outsourcing companies in games, and handle a variety of aspects in game development across art, engineering, functional testing, audio recording, translation, localisation, and player support. They are also one of the largest outsourcing teams now for AI in games, and as such they are building their own ‘AI centre of excellence’ across their business as part of their own Innovation Team. The goal is to help build greater knowledge and consensus within the company of the impact of AI in the sector, and to establish how their practices may need to adapt to suit.

Origins of Project AVA

AVA is a game developed as a collaboration between the Innovation team and their internal development teams. The project was led predominantly by Electric Square, out in Malta, with support from Lively, Lakshya, Liquid Development, Mighty Game, Snowed In Studios and Smoking Gun. The project itself was built to try and gain some stronger understanding on how generative AI can be adopted in games, and largely focussed on three aspects:

Could generative AI create a meaningful percentage of the code and assets used in the game?

Could generative hit a level of quality that the development team would consider shippable?

Lastly, would it be possible to build something that Keywords lawyers would consider shippable?

The project coordinators were aware going in of the legal, and ethical considerations surrounding the use of generative AI. Ranging from the commercial and legal viability, IP and copyright ownership, and of course the concerns of the individual developers working on it. As such, the goal of AVA wasn’t to create a product to take to market and make money from. Keywords is an outsourcing company: it seldom makes its own games, much less ship them. Rather, the goal was to learn as much as they could about whether it is even feasible at this time to ship a game using generative AI tools.

And so at GDC 2024, Stephen Peacock (Head of Game AI) and Lionel Wood (Studio Art Director, Electric Square) delivered a summary of the experiences or themselves and their team in trying to bring AVA to life.

About the Game

Project AVA is a visual narrative game, in which players exist within a science fiction setting with a storyline focussed on the identifying and collaborating with allies across an intergalactic empire. This not only drives the story forward, but also helps identify traitors to imperial rule. The game takes place entirely in dialogue conversations between characters as you move between them across the UI.

Outside of what is described above, there is little more that we know of the game or the quality of the final product. As mentioned already, given it was a research project that was never intended for shipping, it means we can only really piece together the moment-to-moment experience from what was discussed in the talk and the screenshots shown through the presentation*. As such, while Keywords describe this as a complete game, the qualitative value of it is open to debate.

* The presenters had a playable demo running on a laptop, and they offered to show it attendees after the talk. Sadly I missed out given I had to run off to a meeting. #ThatGDCLife

The Right Tool for the Job

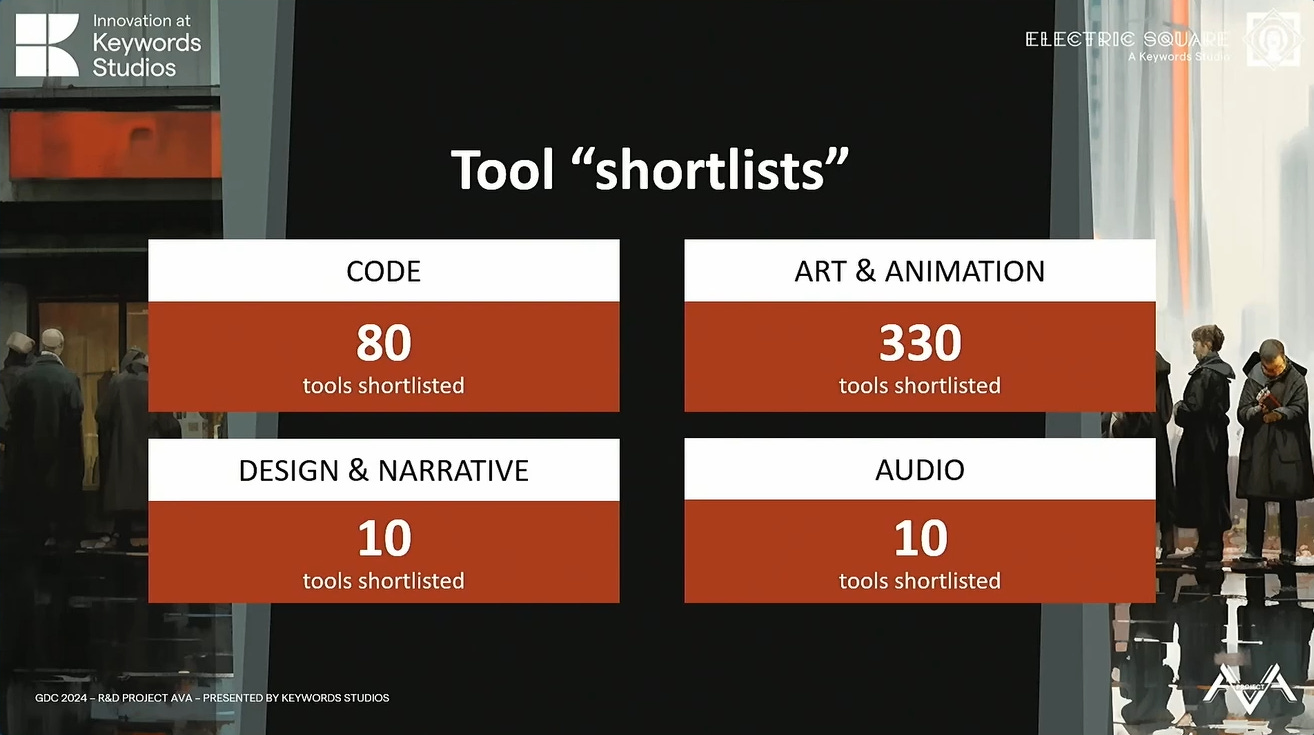

Of course if your goal is to build a game using generative AI, you need to find the right tool for the job. There are hundreds of companies popping up across the sector offering AI tools for various aspects of creative arts and game development. But separating the wheat from the chaff is an ongoing challenge, be it in identifying tools that are actually useful, have reasonable costs for a studio to take on, and of course the underlying terms and conditions of its usage.

As discussed in my recent story on the risks involved for studios to adopt generative AI, companies are going to do their due diligence on the viability of any and all tools. Be it with regards to costs, viability in the production pipeline and tech stack, but also the legal issues that surround it. The confidentiality of assets being used as part of the generative process, the IP and copyright of generated assets, and what contract exists between tool provider and user in terms of protections and rights.

AVA’s original shortlist had over 400 tools listed, spread across code (80), art & animation (330), design and narrative (10), and audio (10). While the viability of the tool and the legal considerations were paramount, ethical considerations were also taken into consideration. Was the team happy with using the tool? Did they need to start thinking of good practice and guidelines for its usage?

While a final number wasn’t provided, it was clear from the presentation that a lot of these tools were almost immediately disqualified due to poor business operations. This included things such as broken websites, costs that could only be shared by consultation, and terms and conditions that were described as ‘comical’, which no legal team would be happy to approve.

The Skill Issue: Prompt Engineering

An observation made by the team throughout their time working on AVA was the need for everyone to better understand how to conduct prompt engineering. Perhaps even more interestingly was the challenges faced in skilling up the team and maintaining their skillset throughout development.

For those not familiar with the term, when we interact directly with text-based AI systems such as GPT, Stable Diffusion and more, we need to consider not just what we ask the system, but how we ask it. After all, generative AI systems don’t understand language like humans do. Users need to more explicit in what they want, how it should be presented, and even force the system to fact check its own mistakes.

While it may sound rather sensationalist, ‘prompt engineering’ is a new skillset that has emerged in the era of text-based interactions with AI systems. Understanding how to get the best out of a text generator like GPT, or an image generator like Stable Diffusion or Midjourney, is slowly becoming an established practice. As such, it’s important for those looking to engage with these systems to understand how to maximise the overall quality of generated outputs. Speaking from experience, I have ran training courses on prompt engineering for game developers in recent months, given it’s not well understood at this time that this is a skillset you may need to learn.

One interesting observation made by the AVA team however, was the need to be maintain prompts as tools evolve. Newer versions of an AI system will often mean that many of the existing prompts don’t work as effectively as before, and may require further research to discover how to get the same (or similar) outputs from the system. Some prompts may no longer get remotely similar outputs if the underlying architecture changed drastically. As such, it proved a challenge at times for the team to keep up with the accepted standards for good prompts as tools changed throughout the development cycle.

This is a small, but actually really important issue for a game developer. Given it’s rare when a game is developed for any external tools or middleware used as part of the production to be updated during development. During early phases of production, a team will decide on accepted versions of specific engines and tools, and only with significant research - and possibly with a small team dedicated to testing it on a ‘branch’ of the project - will a tool be updated during development.

Why is this significant? Because updating tools introduces unnecessary risks during production. As I have discussed previously, game development is vey risk-averse. Speaking from experience, an updated tool can lead to significant disruption to a project if it’s not handled carefully, and of course if due diligence isn’t taken to ascertain whether you should be updating at all!

This highlights a real issue for generative AI companies to consider when working with games studios: ensuring that established behaviours of your systems are still viable and available for developers throughout, and that by default, a tool is not updated for those end users without their consent and approval.

Needing the Human Touch

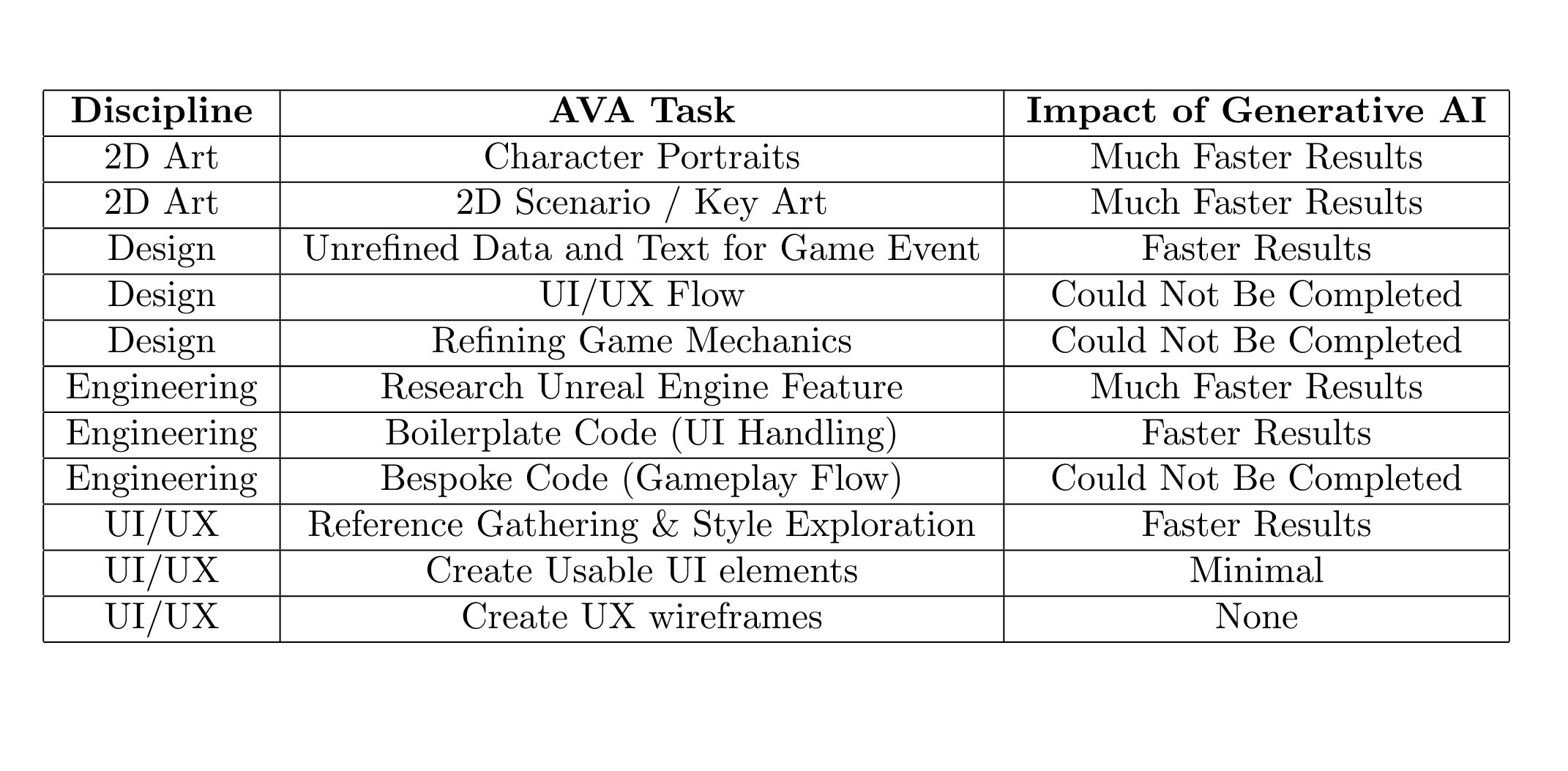

In summary, the team came to a number of interesting conclusions about the viability of AI tools across disciplines, which I summarise in the (screenshot of a) table below.

While the AVA team was happy in that they succeeded in actually building a game within a relatively short timeframe, they acknowledge that it failed to achieve its primary goals. While a significant proportion of assets were created using generative AI tools, they couldn’t reach the desired threshold. Meanwhile, the level of quality did reach an acceptable level, but this was often due to humans taking on these tasks after failing either to find a tool that could achieve it, or getting an adopted tool to deliver at the desired quality. Lastly, the game was not considered to be shippable from the perspective of the legal team.

But throughout the presentation, Wood highlighted that regardless of the quality of the tools, the final product was a reflection of the creativity of the development team, and that critically the best output of these systems was only attainable courtesy of their input. As such, while generative tools helped craft much of the overall experience behind Project AVA, it is still fundamentally a task that requires game developers to use their own creative skillsets to get the very best out of it.

Digging in Deeper

If you want to learn more about AVA, I recommend watching the full presentation. You can find it available to watch on the Keywords website via this link. It is also available on the GDC Vault.

Wrapping Up

Well that’s us for this week. AVA is perhaps the most significant example I have seen thus far of games being developed extensively using generative tools. We’re still at a time where standards and consensus on what are ‘good’ generative AI tools for games is yet to be established. It’s only going to be through experimentation, and critically the sharing of results and outcomes from these processes, that such consensus will begin to form.